Impact cratering on Earth

Until recently, impacts by extraterrestrial bodies were regarded as an interesting but, perhaps, not an important phenomenon in the spectrum of geological process affecting the Earth. Our concept of the importance of impact processes, however, has been changed radically through planetary exploration, which has shown that virtually all planetary surfaces are cratered from the impact of interplanetary bodies. It is now clear from planetary bodies that have retained portions of their earliest surfaces that impact was a dominant geologic process throughout the early solar system. For example, the oldest lunar surfaces are literally saturated with impact craters, produced by an intense bombardment which lasted from 4.6 to approximately 3.9 billion years ago, at least a 100 times higher than the present impact flux. The Earth, as part of the solar system, experienced the same bombardment as the other planetary bodies.

On the Earth, a variety of possible effects have been ascribed to impacts. Currently, the best working hypothesis for the origin of the Earth's moon is the impact of a Mars-sized object with the proto-Earth. This resulted in the insertion into Earth orbit of vaporized material from the impactor and the Earth, which condensed and accreted to form the moon. Heat generated by early impacts may have led to outgassing of Earth's initial crust, thus, contributing to the primordial atmosphere and hydrosphere. Additionally, the impacting bodies themselves may have contributed to the Earth's budget of volatiles. This early bombardment would also have frustrated the development and evolution of early life, with the largest impacts having the capacity to effectively sterilize the surface of the globe. In more recent geologic time, there is evidence that at least one mass extinction event, notably that of the dinosaurs and many other species 65 million years ago, is linked to global effects caused by a major impact event. Impacts also have some economic significance. For example, the vast copper-nickel deposits at Sudbury, Canada are likely a related result of a large-scale impact 1850 million years ago and several impact structures in sedimentary rocks have provided suitable reservoirs for economic oil and gas deposits.

Most of the terrestrial impact craters that ever formed, however, have been obliterated by other terrestrial geological processes. Some examples however remain. To-date, over 160 impact craters have been identified on Earth. Almost all known craters have been recognized since 1950 and several new structures are found each year.

The morphology of impact craters changes with crater diameter. This size-morphology relation is well illustrated with fresh-appearing craters from the moon. Only the smallest impact craters have a bowl-shaped form. As crater diameter increases, slumping of the inner walls and rebounding of the depressed crater floor create progressively larger rim terracing and central peaks. At larger diameters, the single central peak is replaced by one or more peak rings, resulting in what are generally termed impact basins. This same progression in crater morphology is observed throughout the solar system, including on the Earth; although, terrestrial craters are less well-preserved and, hence, more challenging to classify. One notable difference between lunar and terrestrial impact craters is the lower diameter range for each morphological type on Earth. This difference is due to the higher gravity on Earth.

On Earth, the basic types of impact structures are:

(1) simple structures, up to 4 km in diameter, with uplifted and overturned rim rocks, surrounding a bowl-shaped depression, partially filled by breccia.

Alfrancus C - 10 km diameter simple impact crater on the moon (Apollo 16 Panoramic Camera Photograph 4616).

(2) complex impact structures and basins, generally 4 km or more in diameter, with a distinct central uplift in the form of a peak and/or ring, an annular trough, and a slumped rim. The interiors of these structures are partially filled with breccia and rocks melted by the impact.

Tycho - 85 km diameter complex impact crater on the moon (Lunar Orbiter IV photograph 125M).

Schrödinger - 320 km diameter peak ring impact basin on the moon (Lunar Orbiter IV photograph 9M).

Orientale - 900 km diameter multi-ring basin on the moon (Lunar Orbiter IV photograph 194M).

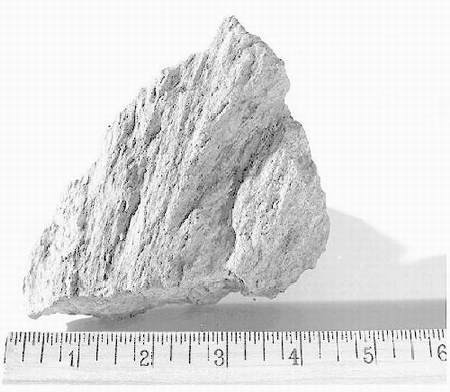

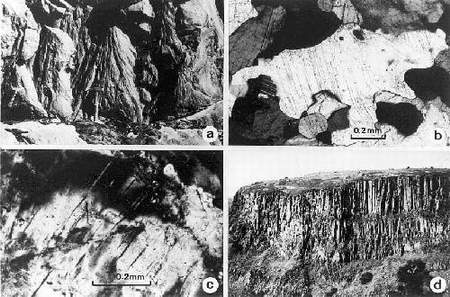

Meteorite fragments are typically found at the smallest craters and they are quickly destroyed in the terrestrial environment. For impact events on Earth that form craters larger than approximately 1 km across, the pressures and temperatures produced upon impact are sufficient to completely melt and even vaporize the impacting body and some of the target rocks, though a small fraction of the impactor can locally be preserved for even the largest impacts. The peak pressure produced by the impact of a stony (chondritic) body into a common terrestrial rock, such as granite, at 25 km per second (a reasonable impact velocity for an asteroidal impact on the Earth) is 900 GPa or 9 million times atmospheric pressure. In such cases, the recognition of a characteristic suite of rock and mineral deformations, termed "shock metamorphism", which are uniquely produced by extreme shock pressures, is indicative of an impact origin. Examples of shock effects include conical fractures known as shatter cones, microscopic deformation features in minerals, particularly the development of so-called planar deformation features in silicate minerals such as quartz, the occurrence of various glasses and high pressure minerals, and rocks melted by the intense heat of impact.

Piece of shatter cone from the Carswell impact structure, Canada.

Shock metamorphic effects of meteorite impact: (a) Shatter cones at the Sudbury structure Canada; (b) Photomicrograph of planar deformation features in the mineral quartz; (c) Photomicrograph of formation of solid-state glass (black) in the mineral feldspar; (d) 80 m thick remnant of the impact melt sheet at the Mistastin structure, Canada.

Although the number of known impact craters on Earth is relatively small, the preserved sample is an extremely important resource for understanding impact phenomena. They provide the only ground-truth data currently available and are amenable to extensive geological, geophysical and geochemical study. Earth's impact craters also provide important data on the structure of such landforms in all three dimensions. In some cases, the large size of terrestrial impact craters, up to approximately 300 km in diameter, requires orbital imagery and observation to provide an overall view of their structure and large-scale context.

The tendency to discount impact processes as a factor in the Earth's more recent geologic history was severely challenged by the interpretation in 1980 that Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) boundary sediments world-wide were due to a major impact event and that impact was the causal agent for a mass extinction event. The acceptance of the K-T impact hypothesis by the more general terrestrial geoscience community was not instantaneous and considerable controversy and debate was generated. Today, there are few workers who would deny that there is abundant diagnostic evidence that a major impact event occurred at the K-T boundary. It is fair to say however, that there is less of a consensus on the role of impact in the associated mass extinction event, with some workers still having difficulty in accepting impact-related processes as the cause.

The impact signal of the K-T event is recognizable globally, because large impact events have the capacity to blow out a hole in the atmosphere above the impact site, permitting some impact materials to be dispersed globally by the impact fireball, which rises above the atmosphere. These materials do not require atmospheric winds for dispersal and have the capacity to encircle the globe in relatively short-time periods, before eventually returning to the surface. Model calculations indicate that it does not require a K-T-sized event, which produced the buried 180 km diameter Chicxulub impact structure in the Yucatan, Mexico, to result in atmospheric blow-out. Relatively small impact events, resulting in impact structures in the 20 km size-range can produce atmospheric blow-out. At present, however, the K-T is the only biostratigraphic boundary with a clear signal of the involvement of a large-scale impact event. The involvement of impact in other boundary events in the terrestrial stratigraphic record has been suggested but little evidence has been offered.

Frequency of impact plotted against energy, either in Joules or Megatons TNT equivalent. Also indicated are a number of impact events. Note an impact event with energy greater than the world's nuclear arsenal occurs on a time-scale of less than a million years.

From estimates of the terrestrial cratering rate, the frequency of K-T-sized events on Earth is of the order of one every 50-100 million years. Smaller, but still significant impact events occur on shorter time scales and will affect the terrestrial climate and biosphere to varying degrees. Even the formation of impact craters as small as 20 km could produce light reductions and temperature disruptions similar to those of a nuclear winter. Such impacts occur on Earth with a frequency of two or three every million years. The most recent known structure in this size range is Zhamanshin in Kazaksthan, with a diameter of 15 km and an age of 1 million years. Impacts of this scale are not likely to have a serious affect upon the biosphere and cause mass extinctions. The most fragile component of the present environment however, is modern human civilization, which is highly dependent on an organized and technologically complex infrastructure for its survival. While we seldom think of civilization in terms of millions of years, there is little doubt that if civilization lasts long enough, it will suffer severely or may even be destroyed by an impact event.

Impacts may also induce chemical changes in the atmosphere. These are related to the vaporization of the impacting body and a portion of the target. Considering only the contribution from the impacting body, recent calculations indicate that even relatively small impacting bodies, < 0.5 km in diameter that produce impact craters on the scale of 10 km in diameter, would inject 5 times more sulphur into the stratosphere than its present content. Larger impact events occurring on the time-scale of a million years will inject enough sulphur to produce a drop in temperature of several degrees and a major climatic shift. There are additional effects on atmospheric chemistry, including the potential for the destruction of the ozone layer from shock heating atmospheric nitrogen and the injection of fluorides from the vaporized impacting body. The threshold for these effects appears to be on the time scale of 100,000's of years.

In marine impacts there is also another consideration; namely, the generation of a tsunami. For example, an impact anywhere in the Atlantic Ocean by a body 400 m in diameter would devastate the coasts on both sides of the ocean with wave runups of over 60 m. The 1960 tsunami, generated by a magnitude 8.6 Chilean earthquake, is thought to have been the largest this century. An impact-generated tsunami 10 times more powerful will occur with a typical recurrence time of a few 1000 years. Small impacting bodies release their energy in the atmosphere, as an air burst. The threshold size at which this is exceeded depends on the strength of the impacting body. For example, iron impacting bodies up to 20 m will deposit their energy in the atmosphere and not reach the surface; whereas, comets as large as 200 m will deposit their energy in the atmosphere. Such air burst explosions, fortunately, are not efficient at delivering their energy to the ground, because some of initial energy is blown into space. The Tunguska event in 1908 was due to the atmospheric explosion of a relatively small, approximately few tens of metres, body at an altitude of 10 km. The energy released, has been estimated to be 10-100 megatons TNT equivalent. Although the air blast resulted in the devastation of 2000 sq. km of Siberian forest (see below), there was no loss of human life due to the very sparse population. Events such as Tunguska occur on a time-scale of 100's of years.

Devastation 8km from ground zero of the 1908 Tunguska event, which was the result of a small asteroid exploding in the atmosphere. Such events occur on time-scales of hundreds of years.

It must be remembered that impact is a random process not only in space but also in time. The next large impact with the Earth could be an "impact-winter"-producing event or even a K-T-sized event. To emphasize this point, in March 1989 an asteroidal body named 1989 FC passed within 700,000 km of the Earth. This Earth-crossing body was not discovered until it had passed the Earth. It is estimated to be in the 0.5 km size-range, capable of producing a Zhamanshin-sized crater or a devastating tsunami. Although 700,000 km is a considerable distance, it translates to a miss of the Earth by only a few hours, when orbital velocities are considered. At present, no systems or procedures are in place, specifically for mitigating the effects of an impact.

Based on an article appearing in Scientific American (Grieve, 1990)

C.R. Chapman and D. Morrison, 1989, Cosmic Catastrophes, Plenum Press, New York, 302 p.

B.M. French, 1998, Traces of Catastrophe, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston, Tx, 120 p. Online version of Traces of Catastrophe (Adobe Acrobat)

T. Gehrels (ed.), 1994, Hazards due to Comets and Asteroids. Univ. Arizon Press, Tucson, 1300 p.

R.A.F. Grieve, 1990, Impact cratering on the Earth, Scientific American, v. 262, 66-73.

A.R. Hildebrand, 1993, The Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary impact (or the dinosaurs didn't have a chance): Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, v. 87, p. 77-118